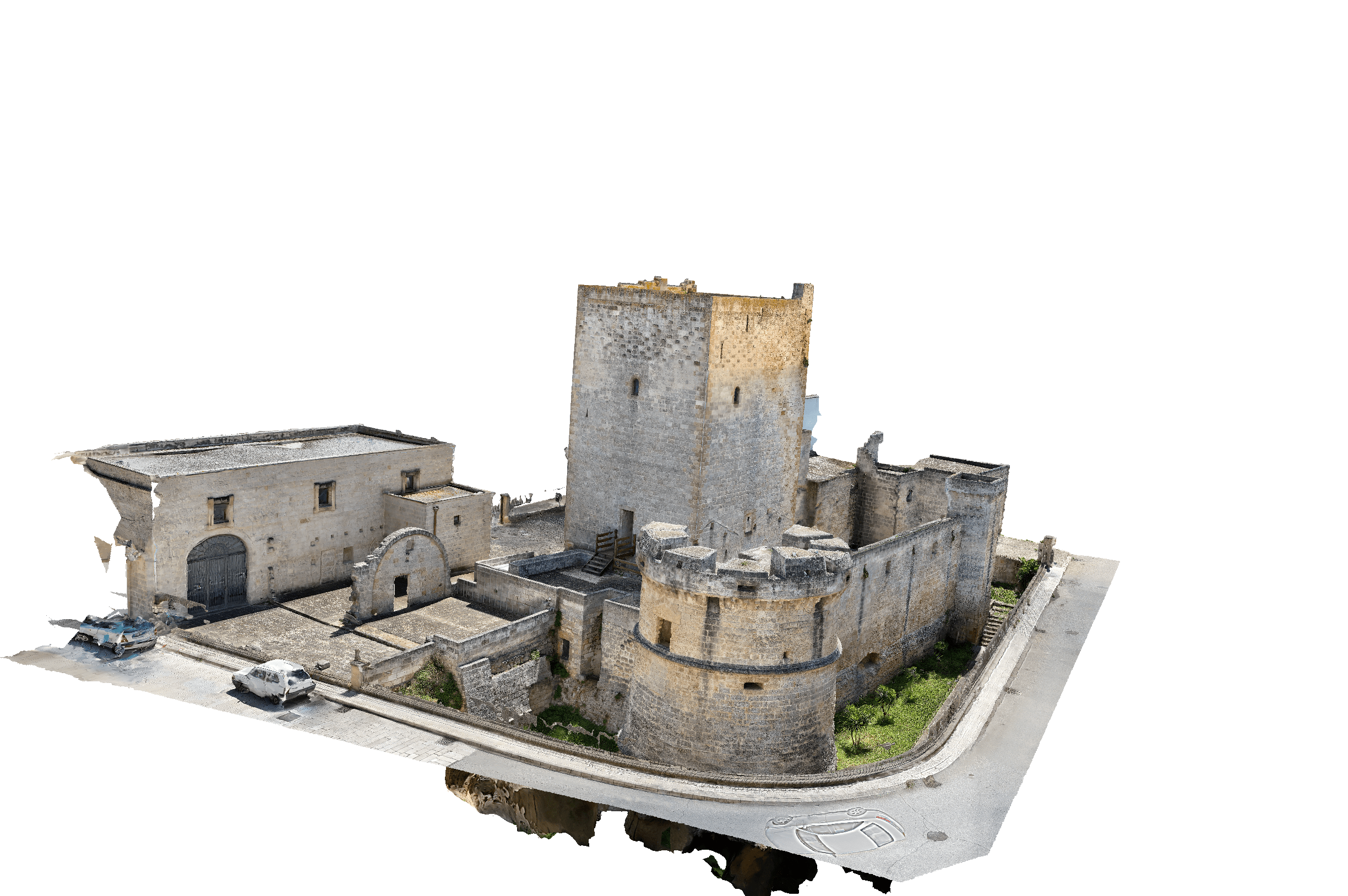

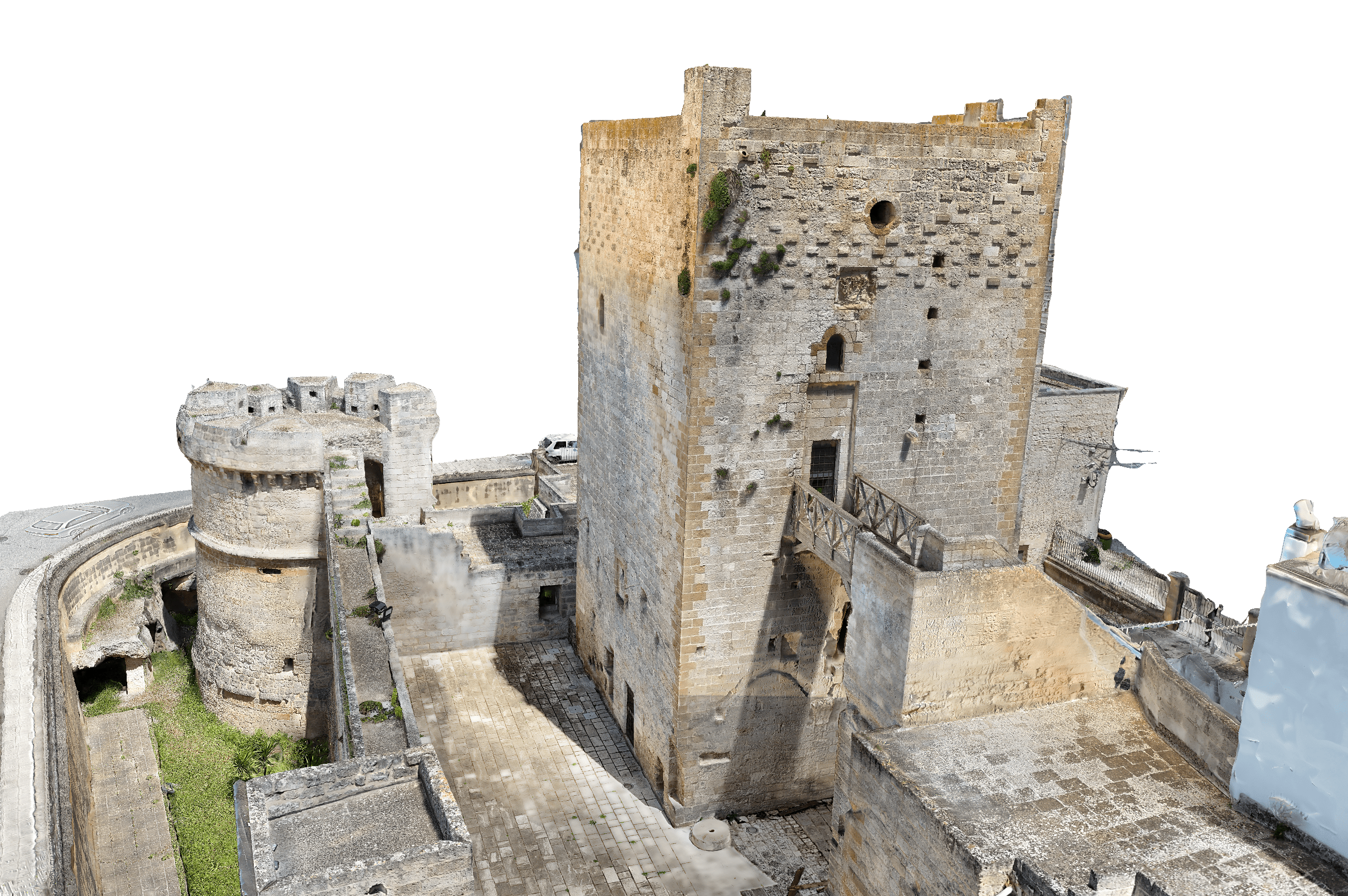

C’è un luogo, nel cuore di Avetrana, dove il tempo ha lasciato la sua firma sulle pietre. Una piazza che non è solo spazio… ma memoria viva. Un teatro senza sipario, dove il popolo ha camminato, lottato, pregato. Amato. Oggi si chiama Piazza Vittorio Veneto. Un nome figlio del Novecento. Ma per secoli è stata semplicemente la Piazza del Popolo. E forse, in fondo, quel nome le appartiene ancora… inciso nell’anima delle sue pietre. Nel Cinquecento, Avetrana era un borgo fortificato. La piazza, più piccola di oggi, era circondata da botteghe, case, rumori quotidiani. E, secondo fonti locali, nel 1644 al centro c’era un pozzo di acqua sorgiva. Una sorgente che dissetava… e univa. Qui le donne si scambiavano parole. Gli anziani raccontavano storie. La vita si faceva comunità. Nel 1793, accadde qualcosa di inusuale. La piazza divenne un tribunale a cielo aperto. Un processo pubblico. Il giudice, l’imputato, la folla tutta intorno. Giustizia alla luce del sole. Era davvero… la Piazza del Popolo. Ogni piazza parla anche attraverso i suoi palazzi. Le sue facciate. I suoi balconi. C’è Palazzo Torricelli. Un tempo convento dei Padri Paolini. Con le sue finestre barocche e balconi ad angolo, riecheggiava di preghiere e di commerci. Poi Palazzo Gaballo: nato come carcere ,trasformato nel Settecento nell’Osteria del Principe Imperiale. Oggi è una dimora elegante, ma porta ancora i segni della fatica e del potere. E poi Palazzo Pignatelli. Sorge là dove un tempo si apriva la Porta Grande, il principale varco d’accesso al borgo, demolita nel 1867. Una soglia simbolica, sospesa tra passato e presente. Nel 1888 si alzò la Torre Civica. Sobria, solenne. Porta un orologio, e una lapide dedicata ai Caduti della Grande Guerra, simbolo di memoria. Dal 1910 al 1959, la piazza fu il cuore del mercato. Le urla dei venditori, l’odore delle olive, il rumore degli animali. Le stoffe colorate al vento. Qui si celebrava anche la fiera di San Biagio, tra processioni, devozione e festa. Negli anni Settanta e Ottanta, la piazza divenne un palcoscenico collettivo. Il Carnevale Avetranese, la Festa della Matricola, l’Estate Avetranese. La sera, tra la pietra calda e le panchine, si intrecciavano storie d’amore, giochi, discussioni. E tante, tante risate. Poi venne il 6 gennaio 1982. La piazza si riempì. Oltre mille persone, arrivate da ogni angolo del territorio. Tutti uniti per dire no alla centrale nucleare che si voleva costruire nelle campagne vicine. Fu una delle prime grandi manifestazioni ambientali della regione. E da quel giorno, molti la ricordano così: “La Piazza dei Mille contro il nucleare.” Una piazza che diventava coscienza. Voce collettiva. Nel 1995, durante lavori di riqualificazione, accadde qualcosa di straordinario. Gli operai sentirono un vuoto sotto terra. Scavarono. E riemersero secoli di storia. Fu scoperto il Trappeto di San Giuseppe: un antico frantoio ipogeo, scavato nella roccia. Per secoli, lì dentro, nel silenzio umido, le olive si trasformavano in olio. Oro liquido. Frutto di fatica, ingegno, trasformazione. Una scala in pietra fu costruita per permettere l’accesso, integrando la scoperta con l’architettura moderna. Nel progetto di riqualificazione . Negli anni ’90, mentre molte piazze italiane venivano semplicemente asfaltate o arredate, ad Avetrana si scelse una strada diversa. Una visione radicale: fare della piazza un’opera d’arte pubblica. Non una piazza “decorata”, ma una piazza che è arte. Un progetto culturale, urbano, emotivo. Il progetto si intitolava: “Le Malie della Strega”. il nome evoca forse un incantesimo, un qualcosa che mira ad influenzare la volontà, ad un forte fascino o attrazione , ad una figura femminile, ad una donna, forse una donna del sud , una forma curva, elegante, ammaliante. lungo la vela nera l'acqua scorre per poi finire in solchi irregolari, capelli fluenti di una fanciulla, o anche segni di un aratro o i graffi della mano di un gigante , per poi finire in una conca a forma di cucchiaio scavata nella pietra ai piedi della vela bianca Il nome del progetto diceva tutto: la piazza come incantesimo collettivo, come gesto poetico e civile. Il progetto come opera diffusa. ideato da Massimo Fagioli, medico e artista, e realizzato dalle architette Anna Guerzoni e Isa Ciampelletti, insieme allo scultore Carlevaro. il progetto comprendeva: La pavimentazione in basole storiche, ripulite e rilucidate. Una balaustra rossa curva che incorniciava l’accesso al trappeto, quasi fosse un sipario su un mondo sotterraneo. Una panchina scultorea a forma di “K”, come un segno astratto ma familiare. Un ulivo secolare piantato al centro: radici nella terra, memoria nel presente. Il graffito “Magia” ideata da Fagioli nel1955 per la staccionata di un complesso residenziale a Prage , e adesso incastonato ad Avetrana nel muro che porta al frantoio , tracciato da linee in movimento rossa . Un impianto spaziale curvo, fluido, in cui nessuna linea è casuale. Tutto nella piazza era segno e significato. Prima della sua realizzazione definitiva, il progetto “Le Malie della Strega” Tra il 1993 e il 1996 . Fece parte di un movimento artistico contemporaneo, che voleva portare l’arte urbana fuori dai musei, fare una mostre itinerante. viaggiò per il mondo. da Barcellona a Tokyo, da Roma a New Delhi, passando per Atene, Singapore, Bangkok, Praga e molte altre città del mondo. Una visione nata per un piccolo centro del sud, capace di mostrarsi alle grandi capitali internazionali. Durante i lavori del 1995, la scoperta del frantoio interruppe il cantiere. Ma invece di nasconderlo, si decise di integrarlo nel progetto. Fu costruita una scala elicoidale a mezzaluna in pietra, affiancata da una parete con il graffito “Magia”, e la balaustra rossa che lo introduceva. Il trappeto, oggi, non è solo un sito archeologico: è parte viva della piazza, cuore pulsante del progetto artistico. È l’inconscio del luogo. Il progetto non era solo urbanistico, ma un’idea di società. La piazza non come centro commerciale all’aperto, ma come spazio di relazione umana, Luogo di memoria e futuro. Crocevia di gesti, emozioni e idee. “Magia” e “Malie” non sono illusioni, ma forme di contatto con ciò che la storia ha lasciato sotto e sopra la pietra. Anche oggi, a distanza di anni, il progetto “Le Malie della Strega” è studiato in contesti accademici e artistici. Un esempio precoce di arte pubblica integrata. La piazza di Avetrana, diventa un’opera totale: un trappeto, una scultura, un manifesto, un documento, un invito. Un luogo che racconta non solo cosa siamo stati, ma cosa possiamo ancora essere. E allora sì: in mezzo al sole del Salento, tra le ombre dei palazzi storici, accanto all’ulivo e alla balaustra, quando ti siedi lì… non sei più solo spettatore. Sei parte dell’opera

There is a place, in the heart of Avetrana, where time has left its signature upon the stones. A square that is not just a space… but a living memory. A theater without a curtain, where the people have walked, struggled, prayed. Loved. Today, it is called Piazza Vittorio Veneto— a name born of the 20th century. But for centuries, it was simply the Piazza del Popolo. And perhaps, deep down, that name still belongs to it… etched into the soul of its stones. In the 16th century, Avetrana was a fortified village. The square, smaller than it is today, was surrounded by shops, homes, the noise of everyday life. And, according to local sources, in 1644 there was a spring-fed well at its center. A source that quenched thirst… and united. Here, women exchanged words. The elderly told stories. Life became community. In 1793, something unusual happened. The square became an open-air courtroom. A public trial. The judge, the accused, the crowd all around. Justice in broad daylight. It was truly… the people’s square. Every square also speaks through its buildings. Their facades. Their balconies. There’s Palazzo Torricelli, once a convent of the Pauline Fathers. With its Baroque windows and corner balconies, it echoed with prayers and commerce. Then Palazzo Gaballo: born as a prison, transformed in the 18th century into the Osteria del Principe Imperiale. Today, it’s an elegant residence, but still bears the marks of toil and power. And then Palazzo Pignatelli, standing where the Porta Grande—the main entrance to the village—once opened, demolished in 1867. A symbolic threshold, suspended between past and present. In 1888, the Civic Tower rose. Sober, solemn. It bears a clock, and a plaque dedicated to the fallen of the Great War— a symbol of memory. From 1910 to 1959, the square was the beating heart of the market. The cries of vendors, the scent of olives, the sound of animals. Colorful fabrics fluttering in the wind. Here, the San Biagio fair was also celebrated, with processions, devotion, and festivity. In the 1970s and '80s, the square became a collective stage. The Avetranese Carnival, the Matricola Festival, the Avetranese Summer. In the evening, between warm stone and benches, love stories, games, debates intertwined. And many, many laughs. Then came January 6, 1982. The square filled up. Over a thousand people, from all over the area. All united to say no to the nuclear plant planned for the nearby countryside. It was one of the region’s first major environmental protests. And since that day, many remember it this way: “The Square of the Thousand Against Nuclear Power.” A square that became consciousness. A collective voice. In 1995, during renovation works, something extraordinary happened. Workers felt a hollow beneath the ground. They dug. And centuries of history resurfaced. The Trappeto di San Giuseppe was discovered: an ancient underground oil mill carved into the rock. For centuries, within its damp silence, olives were turned into oil— liquid gold, born of labor, ingenuity, transformation. A stone staircase was built to allow access, integrating the discovery into the modern architectural project. In the 1990s, while many Italian squares were simply paved or furnished, Avetrana chose a different path. A radical vision: to make the square a work of public art. Not a “decorated” square, but a square that is art. A cultural, urban, emotional project. The project was titled: “Le Malie della Strega” (The Witch’s Charms). A name that perhaps evokes a spell, something that seeks to influence the will, a powerful charm or attraction, a feminine figure, a woman— perhaps a woman of the South, a curved, elegant, bewitching form. Along the black sail, water flows, ending in irregular furrows— flowing hair of a maiden, or the tracks of a plow, or the scratches of a giant’s hand— culminating in a spoon-shaped basin carved into the stone at the foot of the white sail. The name of the project said it all: the square as a collective enchantment, a poetic and civil gesture. The project as a diffused artwork, conceived by Massimo Fagioli, physician and artist, and realized by architects Anna Guerzoni and Isa Ciampelletti, together with sculptor Carlevaro. The project included: Historic flagstones, cleaned and polished. A curved red railing framing the entrance to the oil mill, as if it were a curtain to an underground world. A sculptural bench shaped like a “K”—an abstract yet familiar symbol. A centuries-old olive tree planted in the center: roots in the earth, memory in the present. The graffiti “Magia,” designed by Fagioli in 1955 for a residential fence in Prague, now embedded in Avetrana on the wall leading to the oil mill— red lines in motion. A curved, fluid spatial design in which no line is accidental. Everything in the square is symbol and meaning. Before its final implementation, Le Malie della Strega—between 1993 and 1996— was part of a contemporary art movement that sought to bring urban art outside museums, to make a traveling exhibition. It traveled the world: from Barcelona to Tokyo, from Rome to New Delhi, passing through Athens, Singapore, Bangkok, Prague, and many other world cities. A vision born in a small town of the South, able to present itself to major international capitals. During the 1995 works, the discovery of the oil mill interrupted the construction. But instead of hiding it, they chose to integrate it into the project. A crescent-shaped spiral staircase was built in stone, flanked by a wall with the Magia graffiti, and the red balustrade that introduces it. Today, the oil mill is not just an archaeological site: it is a living part of the square, the beating heart of the artistic project. It is the unconscious of the place. The project was not just urban planning—it was a vision of society. The square not as an open-air shopping center, but as a space for human connection, a place of memory and future, a crossroads of gestures, emotions, and ideas. “Magia” and “Malie” are not illusions— but ways of connecting with what history has left beneath and above the stone. Even today, years later, the project Le Malie della Strega is studied in academic and artistic contexts. An early example of integrated public art. The square of Avetrana becomes a total work: an oil mill, a sculpture, a manifesto, a document, an invitation. A place that tells not only what we have been, but what we can still become. And so yes—under the Salento sun, amid the shadows of historic buildings, beside the olive tree and the balustrade— when you sit there… you are no longer just a spectator. You are part of the work.